So the curtain has come down on Pacific Northwest Ballet‘s first-ever digital season—although a Season Encore performance will be available June 18-22 ($29).

Rep 6 was the final regular season program, though, featuring two world premieres: Christopher Wheeldon’s Curious Kingdom and Edwaard Liang’s Veil Between Worlds, and the PNB premiere of Alejandro Cerrudo’s PACOPEPEPLUTO (2011). All were broadcast in 1080p, a decision that rankled with me since our prolonged stint indoors finally led me to upgrade to a 4K television. That misstep aside, the film team deserves kudos for their work over the season. The multi-camera approach PNB is affectingly immersive, especially for solos and pas de deux when the dancers are right there, filling the screen, and in quieter moments you can hear the subtle squeak of their ballet shoes in turns. That said, this program’s editing was not quite as seamless as it has been. I counted about five transitions that were either slightly mistimed, or that jarred with changes in fields of view so you had the feeling of a superfast zoom.

Part of the excitement of world premieres is whether there is the opportunity to pronounce one or more of the works an instantly accessible masterpiece—here, it turns out, no. Both works had memorable facets, but none managed to crystallize into a stirring, defining-a-moment whole, despite repeated viewings. Not everything good is ‘instantly accessible’, of course—sometimes greatness only become apparent in the rearview mirror, as with Citizen Kane or The Big Lebowski.

Wheeldon’s Curious Kingdom was the most formally inventive, if also remarkably earthbound for its first half, with an almost algorithmic execution of styles of port de bras. Sheathed as they were in skintight, glistening silver unitards with the look of strapless bodices up top (Harriet Jung and Reid Bartelme’s designs), the dancers could at times look like fronds waving in a vase, an effect heightened by red gloves. The first part was set to Satie’s Ogive No. 4, the meditative-not-to-say-soporific Gnossiennes 1 and 2, and Avant-dernières pensées, then from Ravel’s Miroirs, “Oiseaux tristes” and “La vallée des cloches”.

At the outset, all five dancers appear in silhouette in a wash of golden light; standing in a mirror-like rectangle of floor, they flap their arms briefly, step forward with a chin-up, yearning carriage, and then deflate. Movements, gestures, seem to descend with the piano keys, chiming. Later, with a foot behind, they cantilever their torsos back. You’ll see this movement again in the second part, Lucien Postlewaite in majestic Red Queen drag as Piaf sings “Non, je ne regrette rien”, bending almost parallel to the floor before flipping then sinking into a naturalistic, floor-scraping bow, arms sweeping out to accept plaudits. Postlewaite’s red-gloved hands, floating about his face as if controlled by strings, also turn into a flower opening, or a crown (his head dipped out of view), form a heart over his chest, then sheer into two pieces.

(Sidebar: Is there a ballet of Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night? Oh, there is. Great, well, may I suggest Wald and Macy as the leads for you. Oh, planning the season is Peter’s job? I suppose casting is, too? Fine! *throws up hands*)

It is not all impressionist portraits: Dylan Wald and Elle Macy appear for pas de deux in both parts, sharing a pair of red gloves (in the second, with the addition of a large red tulle bow on each of their backs), and although the movement vocabulary is still angular and shape-driven, there is a fascinating shared journey through space. Of the more striking moments: with arms out and hands joined, creating a box, the two gently rotate their head around the other’s; then one standing, leg lifted, knee bent, and the other on the floor, knee down, foot pointed up, a diamond is formed. You think flamingo, naturally, but I think you’re also meant to remember flamingo croquet.

Similarly, Jerome Tisserand’s elegant, Swiss watch-work rotations across the stage are joined to a sort of mimed, playing-card-shape. Then Leta Biasucci bursts upon the stage, en pointe in a gray tulle skirt, dancing with an almost Red Shoes energy, only here they are elbow-length red gloves. Reed Nakayama’s lighting-as-set-design reaches whimsical, minimalist heights with a pool scene generated largely by the color teal and the two very amiable dancers wearing red bathing caps.

Are you having any difficulty integrating this floral-aquatic, French impressionist-Piaf, non-binary, esoteric-Alice in Wonderland, TikTok dance (okay, not that but would it surprise you?) because I struggled to pull all of these pieces together. It has been a long pandemic. I have been writing myself into an appreciation of the work, but it still seems like a lot to take in, and I believe the program notes were four lines.

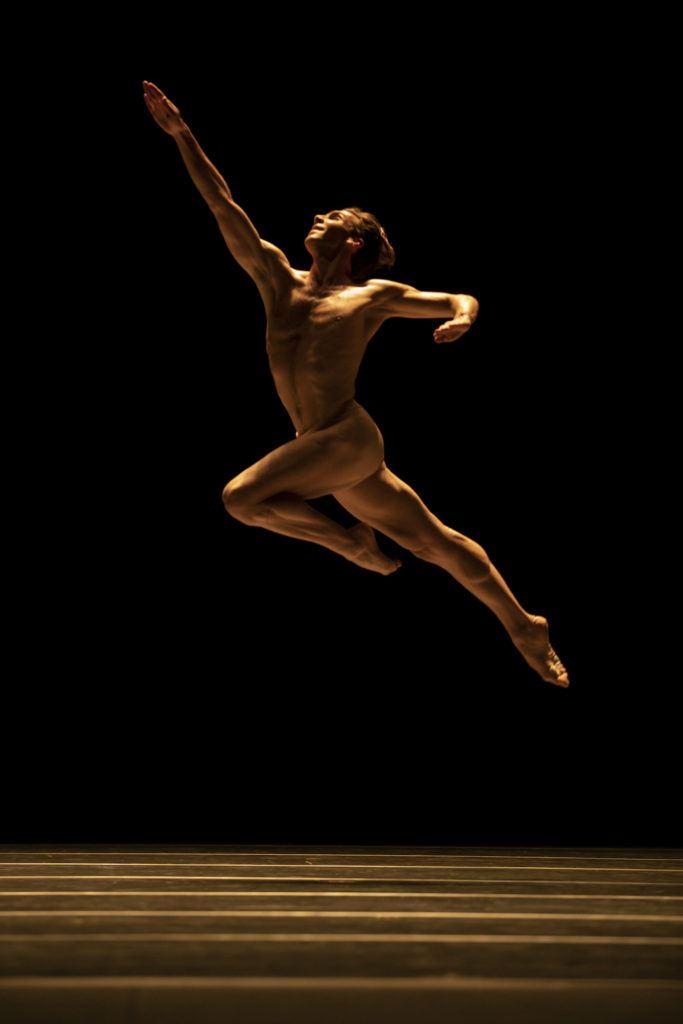

I’ll mention what I didn’t like about Cerrudo’s short provocation PACOPEPEPLUTO first, to get that out of the way, and it’s just that it was difficult to discern what three Dean Martin crooner-era songs (“In the Chapel in the Moonlight”, “Memories Are Made of This”, and “That’s Amoré”) had to do with the three solos by dancers on an ominously dark stage wearing only a dance belt (and who, from the mimed protective crotch gestures, might be meant to be taken as fully nude).

Otherwise, I have seen thirty-minute dance pieces with fewer choreographic ideas than this 8-minute profusion—it’s the 90-page Moonlighting script of dance, with no phrase actually coming to a rest: there’s always a twist, hop, shimmy, or turn, and it sprints off in another direction (ironically, things only ‘end’ when the dancer runs off). Christopher D’Ariano gave a Stretch Armstrong macho-ballon performance, James Yoichi Moore’s had a little head-banging and cartoon cock-of-the-walk strutting, and Lucien Postlewaite was a sinuous Grecian-urn athlete and jittery as Elvis in love (clamping down on a shaking hand but watching his foot twitch instead). I don’t want to over-theorize here but the primordial nudity and the ’50s bachelor-pad soundtrack do come together in a way that gets at something about the history of male pride and bodily exhibition…oh, but I see your eyelids are drooping. I’ll save it for my Substack longform.

Edwaard Liang’s Veil Between Worlds also came with gauzy about-the-work notes that invited you to “join with the dancers in their creative universe” but it would be an invidious comparison (that’s right, I’m trying to bring invidious back) to contrast Liang’s neoclassical style with the experiment of Wheeldon, no matter what the New York Times tells you. I’m more interested in what the work means to say, and Liang’s oracular notes about “perceived reality and fantasy” struck me as out-of-step with our current drowning-in-pandemic-conspiracy-theory scenario.

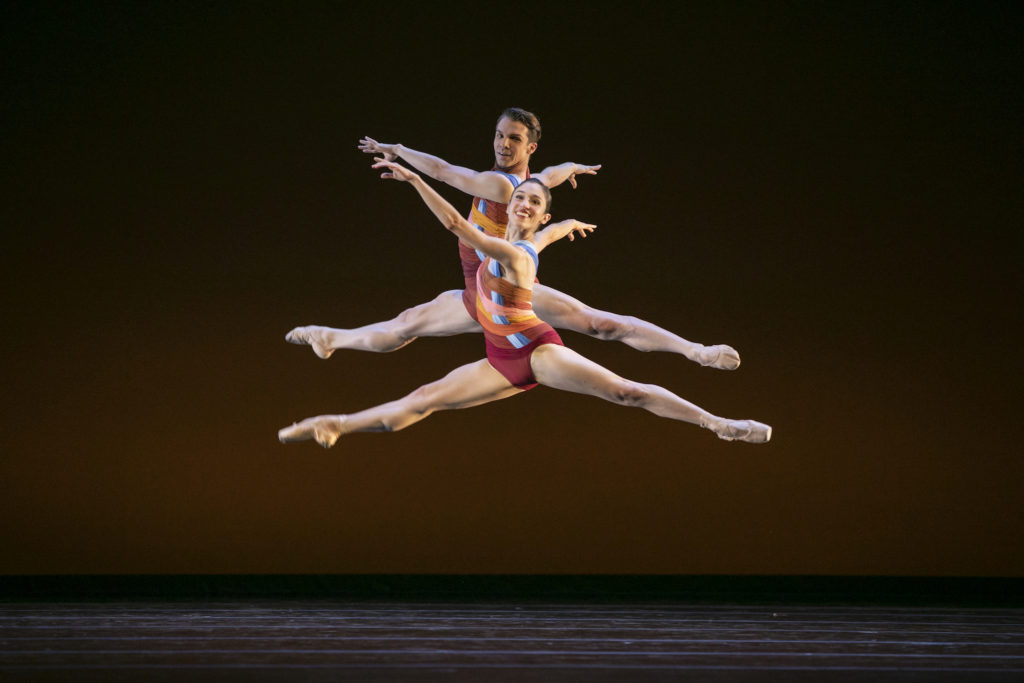

Nonetheless, it’s a likable and entertaining work, despite it not following through on the spectacle of its opening (pictured above). A few seconds before, Laura Tisserand was giant-sized, wearing the cloth material like a dress—in a theatre you’d have heard gasps. Her pas de deux with Jerome Tisserand, filled with long slides, petit pas, and lifts was a welcome, graceful respite from the notion of obstacle. There is a good deal of cheerfulness, with duos, trios, and foursomes (the whole cast delighting in, from all appearances, Liang’s light-footed choreography), but also a fugue-like transferring of movement that perhaps hinted at something else; if you listen to Oliver Davis’s propulsive, motoric score, with quick bowing from the strings, there’s not much distance between gaiety and a mask with a smile on it.

Dylan Wald shot out from beneath the material to dance something with a bit more intensity, and I thought for a second I saw a Hamlet-like ‘Alas’ gesture but his curved right arm continued past his head, and the little shiver vanished. Normally impressed by Mark Zappone’s costume design, I was a little nonplussed by these, which suggest late ’70s Olympic gymnastic team.