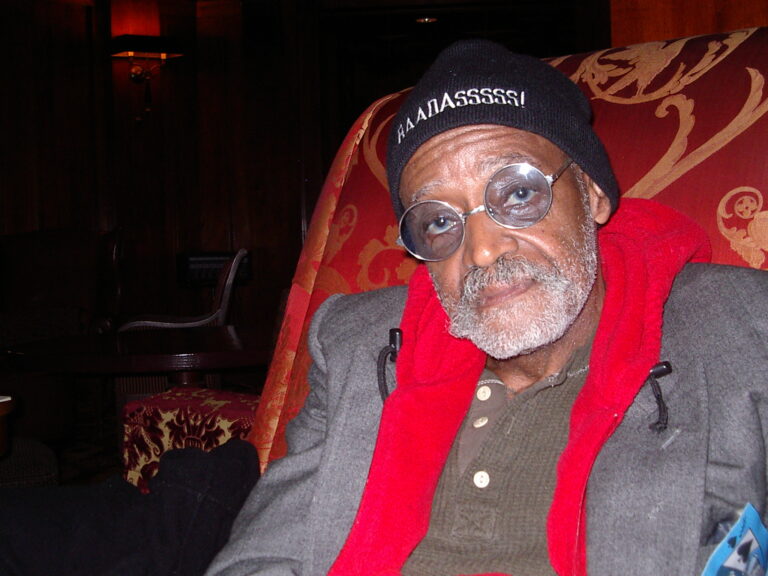

It’s 12:30 p.m. on Labor Day, and legendary director/writer/artist/iconoclast Melvin Van Peebles is running about a half-hour late.

I’m slumped comfortably in a cushy red velvet chair in the lobby of the Sorrento Hotel, poring over my notes and questions as soft orange-yellow light marinates the mahogany-paneled walls. The color scheme and the illumination lend a high-class velour soul feel to the mission-style architecture: Then again, an impending interview with a key figure in the evolution of 1970’s cinema has a way of influencing your perceptions.

Nervousness rears its head a bit as I wait. After all, this is the director of one of the most fierce socio-political statements put to film; a man famous for his activism, for his refusal to compromise, and for not suffering fools gladly. I’ve talked to a fair amount of artists over the years, but I’m a little afraid—just a little—that this one might hand me my ass on a paper plate if I don’t have all my ducks in a row. Here goes nothin’, I think as the Sorrento’s elegant glass doors open and Melvin Van Peebles walks in, backpack slung over his shoulder.

For a man whose legend looms so large, he’s surprisingly genial in appearance. A ready, genuine smile crosses his white-bearded face: That grin, his layers of clothes, and his gloriously loud sneakers serve notice that this man marches to the rock-steady backbeat of his own drummer. Van Peebles shakes my hand vigorously and apologizes for his late arrival in the sincere tones of a man not prone to wasting his (or anyone else’s) time.

He’s barely hit the door when he plops onto one of the Sorrento’s soft red velvet couches, ready to jump right in. As I very quickly learn, this seventy-some-year-old guy never slows down. Ever.

“What do you want to talk about?” Van Peebles says with a smile. His steely eyes flicker, sharp and alert.

I extend congratulations to him for the flurry of lifetime accolades he’s received in recent years (Lifetime Achievement Awards at the Los Angeles Pan African Film Festival and the Chicago Underground Film Festival, among others). “Actually, [the recognition’s] really not important,” He counters good-naturedly. “I have a mirror. And I look at me in the morning, I say hi: ‘Hi!’ That’s good enough.”

Van Peebles is much more interested in talking about his new movie, Confessions of a Ex-Doofus Itchy-Footed Mutha. He reaches into his backpack and produces the graphic novel that he’s created in tandem with the movie, showing the book off and enthusing about the combination of movie images and illustrations that pepper it. The proud papa surfaces when it comes to the movie represented in these four-colored pages, and he’s a little frustrated that the critical cognoscenti don’t seem to get it.

“Some of the early reviews of the film say, ‘Well, it’s fine but it uses tacky visual effects.’ Those are not tacky effects,” he states emphatically. “It’s very shocking that people—especially the people that claim to be on-point—want everything smoothed out. And I left it that way intentionally.”

I point out one of the most impressive things about the movie for me—its ambitious and sprawling narrative. He admits that he’d planned that breadth of scope all along, and that putting a black man at the center of the story holds extra resonance. “I shot it all around the world…in Zanzibar, Kenya, the Caribbean, all over; just wherever I wanted to.

“If you’re making a ‘colored movie,’ a Negro movie, you never go beyond 110th Street and 115th. Get the fuck outta here! Gulliver gets to go around; Canterbury Tales gets to go around; Dante’s Inferno

gets to go around the world. Everyone else gets to go places, so I thought it’d be really great to…see the world through this character’s eyes. And gradually, his humanity expands.” Van Peebles also prides himself that his principal character speaks in iambic pentameter throughout the entire movie (another fact lost on most critics).

He eloquently defends his choice to play the main character from the age of ten to the age of forty-something. “If you’re talking to your kids, or your grandfather’s talking to you about his younger years, you don’t see a young man, you just see your grandfather a little smaller, a little less gray, you know what I mean?” he notes with a hearty chuckle. “That was part of the message: When he grows up, he’s still the same guy.”

The character Van Peebles plays in Confessions bears more than a little resemblance to the man himself: A streak of wanderlust runs through both of them. Before becoming a film director, Melvin served in the Air Force during the Korean War as a navigator, painted portraits in Mexico, worked San Francisco cable cars as a gripman, and tried on a journalistic career in France.

He mastered the mechanics of filmmaking by trial and error, literally learning basics like editing, which film stock to use, and post-production dubbing on the fly. Eventually he produced a couple of short films that made a strong impression on the French.

“The French saw these first two short movies I did, and they said, ‘You’re a genius!’ They wrote me a letter. I was a nobody, and they’d seen these movies sort of by accident. So I went to France.”

Unfortunately, the reality of his visit contrasted harshly with the romantic surroundings. “Usually when somebody invites you to a university, they put you up and so forth. Here, they kissed me, looked at my films, and that was that…It was August 1960.

“As we came out of the theater, the lights on the Champs-Elysées had just come up. Everyone was applauding me, telling me what a genius I was. But I didn’t have a way home,” He laughs. “I was in the fucking middle of the Champs-Elysées; can’t speak a word of French; I’ve got three cans of film, two wet cheeks; and empty pockets. But they’d done the most important thing, which was to give me hope.”

The budding filmmaker plugged away for a few more years in France, (literally) begging, borrowing and stealing to stay alive. Then he shot his first feature, La Permission (aka The Story of a Three-Day Pass) in 1967. The gentle comedy about an African-American GI who falls in love with a Parisian shop clerk wowed judges at the San Francisco Film Festival with its subtle European flavor.

“I came back to San Francisco as the French delegate in the 1968 San Francisco Film Festival. No one knew I was an American, let alone black. I got off the plane, and the woman talked to me in French: ‘Melvin Van Peebles? Delegation Française?’ I said, ‘Lady, don’t bother me.’ ‘Melvin Van Peebles?’ ‘Yes, I’m Melvin.’ ‘YOU’RE the French delegate?’ I said, ‘That’s me!’ And then the film won the San Francisco Film Festival’s Critic’s Choice Award.”

Hollywood studios smelled potential Next-Big-Thing status based on the buzz, and after fielding offers from various producers he settled on a project with Columbia Pictures, the topical comedy

Watermelon Man. In it, Godfrey Cambridge plays a racist white man who wakes up black one morning and rapidly finds himself on the receiving end of racism from society, his employer, and his wife. It blazed trails aesthetically.

“In the original story the guy woke up again, and he was white: It had all just been a bad dream. I said, ‘No, he should stay black.’ The subliminal message is that black is just a nightmare, you know? We went around and around, and [the studio] agreed we should shoot it two ways, and see which way works better. So that’s what I agreed to. However, I lied and cheated and only shot it my way.”

Just as importantly, Watermelon Man made Melvin Van Peebles a trailblazer behind the camera. Talents like Ossie Davis and Gordon Parks had already directed Hollywood features, but “those films were shot on location—that is, away from ‘the castle’ itself,” Van Peebles divulges with a conspiratorial whisper. “I said that I’d shoot [Watermelon Man] on one proviso: That we shoot it in Hollywood itself. Because I thought that was the next wall that had to be broken down.” The upstart director became the first African American to shoot a Hollywood feature on an actual Hollywood soundstage.

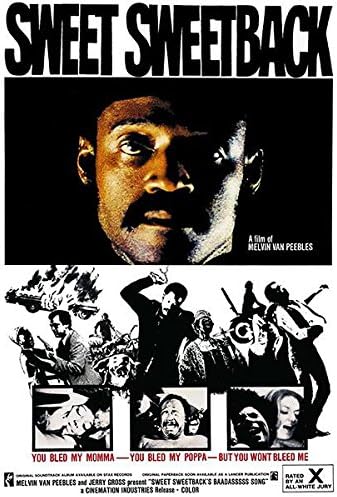

His proceeds from Watermelon Man provided the seed money for what would prove to be Melvin Van Peebles’ most world-shakingly influential effort, Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song. Ostensibly, the 1971 movie details the saga of a sex performer (played by Van Peebles) who finds himself on the run from the law after coming to blows with corrupt white cops. But Sweetback marked the first time in screen history that an African-American defiantly faced racism and lived. It’s Melvin Van Peebles’ song for the ages—a crudely-shot, willfully ragged, passionate, angry, and purposeful middle finger thrust in the direction of The Man; alternately exploitive as hell, and one of the most politically-galvanizing films to emerge from the ‘70s.

The making of the movie is the stuff of cinema legend, an odyssey of incalculable financial risk for Van Peebles (he essentially torpedoed a lucrative three-picture deal with Columbia by filming Sweetback), physical duress, the threat of death (his crew frequently carried live handguns for safety), and strange bedfellows (when money for the movie dried up, comedian Bill Cosby jumped in with a $50,000 fund infusion). Van Peebles and his son Mario (an established actor/director in his own right) chronicled the whole saga in the book Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song: A Guerilla Filmmaking Manifesto, and Mario directed Badasssss!, an excellent biopic about the making of his dad’s magnum opus, in 2004.

The elder Van Peebles got to see his success—and his statement—affirmed in a packed Georgia movie house during an opening-weekend screening. “You could’ve heard a rat pissing on cotton in Atlanta; not a sound,” he remembers. “There was only one seat open, next to a little old lady. I managed to sit by her. [Then comes] the scene where Sweetback’s in the desert. She says, ‘Oh, Lord, let him die. Don’t let them kill him.’ It was the greatest moment for me, because up until that time, any black character who stood up always died before the end of the film. It was unimaginable that he was going to live. That was validation with a capital V.” He received ample financial validation, too: Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song grossed over ten million dollars on a $500,000 investment and ensured Van Peebles’ status as a godfather of American indie cinema.

The director followed Sweetback’s mammoth success with—of all things—a musical. Don’t Play us Cheap hit theaters in 1973. In it, two demons attempt to crash a lively Harlem party, only to find their efforts thwarted by the resilient spirit of the revelers. Joyous and uninhibited, Don’t Play us Cheap was inspired by an encounter Van Peebles had with an old lady in Harlem. The director allowed her to use his bathroom one day, and later in the week she invited him to her niece’s birthday party. Something about the partygoers inspired Van Peebles.

“…I thought, what would happen if a devil came in…That was the genesis of that, because…you needed this sense of evil. If you don’t have that sense of evil with the other person, you’ve got no terra firma to fight on in the first place. These devils kept doing what they were doing, so I had all of these scenes where the devils kept trying to do harm, and it kept getting turned around on them. It was great.”

Never one to shy away from a challenge, Van Peebles composed Cheap’s impressive, gospel-drenched songs and score himself without one iota of musical training. I ask him if he sat down with a pianist to work out the melodies, and he reveals that he actually worked alone, numbering the keys on a piano and creating his own method of composition. “…I just numbered all the keys on the fuckin’ piano. I couldn’t write, but I could count!” he says, laughing. After the movie’s theatrical run Van Peebles turned it into a successful Tony-Award-nominated musical.

Since then, the man’s never slowed down. He followed up Cheap with another hit Broadway musical (Ain’t Gonna Die a Natural Death), recorded spoken-word albums widely acknowledged as a major influence on hip-hop, wrote several books, earned a seat on the New York Stock Exchange (the first African-American to do so), directed still more films and TV, and was sampled by scores of rappers. For his next project, he’s looking to go back to the well and adapt his most recent Broadway play, Unmitigated Truth, into a feature. It’s all par for the course for a guy who, at age 76, runs three to four miles a day and maintains a schedule that’d cause cats half his age to collapse in an exhausted heap. “It ain’t how many times you get knocked down that counts, it’s how many times you get up,” he says with a twinkle in his eye.

Before I know it, an hour and fifteen minutes have gone by, and Van Peebles’ assistant gently asks him to wrap up in time for the next interviewer. “He can tell stories forever if you give him half a chance,” she says affectionately. “And it’s easy to get caught up in them.”

Melvin Van Peebles shrugs, offers another hearty handshake, and flashes another warm smile. It’s the same smile that’s likely charmed Hollywood suits, Broadway producers, and scores of ladies with equal efficacy. “I’m sorry about the time. It just got mixed up,” he says as he gets up to leave.

He asks for me to mail him a printed copy of the interview when it’s finished, and he scrawls his mailing address onto my pad. The pen he’s using sports a rubber effigy of Bart Simpson on it, and it quotes bonbons of Bart snarkiness loudly as Melvin writes.

Each click of the pen sounds less like Bart Simpson and more like Melvin Van Peebles’ drummer continuing to pound out that singular beat, I think as I make my way out into the gray afternoon.