Every time one of us wakes up in the morning, there’s a very good chance that the first news story we’ll see is that the President of the United States of America has insulted someone on Twitter, as someone 100 percent secure in their role as the most powerful person in the world does. It’s not just the President. I live in true-blue Seattle and yet I still see bumper stickers that say “Liberalism is a Mental Disorder” daily, and Milo Yiannopolous and Twitter continue to exist. It’s a mean world out there, my friends.

For all of the cruelty we all see day in and day out, it means that Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, the new documentary about the life of Fred Rogers is more welcome and necessary than ever. Mr. Rogers, through his long-running PBS series Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, taught his young viewers (which included me throughout my childhood) that every child is worthy of being loved without having to do anything extraordinary to earn said love. A devout Christian who voted Republican, Mr. Rogers likely provided most children who watched his show with their first exposure to empathy. I believe that to be true of myself.

Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood was a huge part of my childhood, but this passage from a 1998 profile in Esquire magazine has never been too far from my thoughts ever since I read it several years ago:

Once upon a time, there was a boy who didn’t like himself very much. It was not his fault. He was born with cerebral palsy. Cerebral palsy is something that happens to the brain. It means that you can think but sometimes can’t walk, or even talk. This boy had a very bad case of cerebral palsy, and when he was still a little boy, some of the people entrusted to take care of him took advantage of him instead and did things to him that made him think that he was a very bad little boy, because only a bad little boy would have to live with the things he had to live with. In fact, when the little boy grew up to be a teenager, he would get so mad at himself that he would hit himself, hard, with his own fists and tell his mother, on the computer he used for a mouth, that he didn’t want to live anymore, for he was sure that God didn’t like what was inside him any more than he did. He had always loved Mister Rogers, though, and now, even when he was fourteen years old, he watched the Neighborhood whenever it was on, and the boy’s mother sometimes thought that Mister Rogers was keeping her son alive. She and the boy lived together in a city in California, and although she wanted very much for her son to meet Mister Rogers, she knew that he was far too disabled to travel all the way to Pittsburgh, so she figured he would never meet his hero, until one day she learned through a special foundation designed to help children like her son that Mister Rogers was coming to California and that after he visited the gorilla named Koko, he was coming to meet her son.

At first, the boy was made very nervous by the thought that Mister Rogers was visiting him. He was so nervous, in fact, that when Mister Rogers did visit, he got mad at himself and began hating himself and hitting himself, and his mother had to take him to another room and talk to him. Mister Rogers didn’t leave, though. He wanted something from the boy, and Mister Rogers never leaves when he wants something from somebody. He just waited patiently, and when the boy came back, Mister Rogers talked to him, and then he made his request. He said, “I would like you to do something for me. Would you do something for me?” On his computer, the boy answered yes, of course, he would do anything for Mister Rogers, so then Mister Rogers said, “I would like you to pray for me. Will you pray for me?” And now the boy didn’t know how to respond. He was thunderstruck. Thunderstruck means that you can’t talk, because something has happened that’s as sudden and as miraculous and maybe as scary as a bolt of lightning, and all you can do is listen to the rumble. The boy was thunderstruck because nobody had ever asked him for something like that, ever. The boy had always been prayed for. The boy had always been the object of prayer, and now he was being asked to pray for Mister Rogers, and although at first he didn’t know if he could do it, he said he would, he said he’d try, and ever since then he keeps Mister Rogers in his prayers and doesn’t talk about wanting to die anymore, because he figures Mister Rogers is close to God, and if Mister Rogers likes him, that must mean God likes him, too.

As for Mister Rogers himself…well, he doesn’t look at the story in the same way that the boy did or that I did. In fact, when Mister Rogers first told me the story, I complimented him on being so smart—for knowing that asking the boy for his prayers would make the boy feel better about himself—and Mister Rogers responded by looking at me at first with puzzlement and then with surprise. “Oh, heavens no, Tom! I didn’t ask him for his prayers for him; I asked for me. I asked him because I think that anyone who has gone through challenges like that must be very close to God. I asked him because I wanted his intercession.”

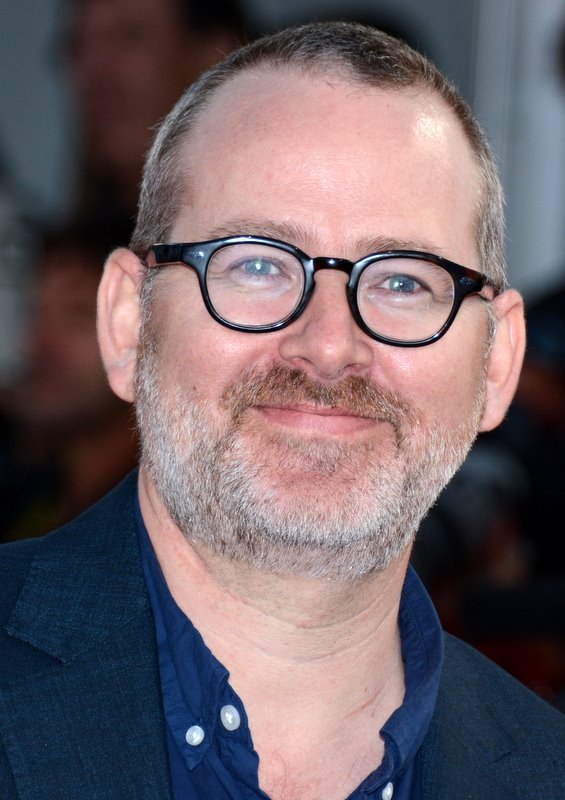

Morgan Neville, an Academy Award-winning director (probably best known for 20 Feet From Stardom), helmed this documentary and it’s a truly special movie about a uniquely special man. Everyone that I know who has seen it has said it made them tear up. It is a remarkable film, and a film-going experience. I don’t know if I’ve ever seen a movie that made me immediately want to become a better person and all that was expected was to practice kindness. Won’t You Be My Neighbor? is about the life of someone who was kind to other people literally all the time. Mr. Rogers died in 2003 at 74, and today a movie about the life of someone who has made being kind to others the main purpose of their life feels like science fiction today.

While he was in town for the two sold-out screenings at the Seattle International Film Festival, I had about ten minutes to speak with Morgan Neville about this film.

What was it about Mr. Rogers that made you want to take on him as a subject. I believe the last time you were at SIFF was for 20 Feet From Stardom, which paid tribute to backup singers who were given long-overdue credit through your film, but Mr. Rogers was his own entity…

I did another film called Best Of Enemies about William F. Buckley and Gore Vidal. Oddly I feel like that film and Mr. Rogers film were very connected because they’re both about television in the same time period. One’s a cautionary tale and one’s a hopeful tale.

Oddly they’re an interesting double feature. One of my big themes I come back to, something I just believe is a crucial issue, is how culture can help us discover common ground. I feel like Best Of Enemies is about the loss of common ground, but Mr. Rogers is somebody who supersedes labels and tribalism, and that everybody’s relationship with him predates our sense of self. He’s somebody who also is talking about basic principles of how we should live together and how we should treat each other, which are the things that you think anybody can subscribe to these days. Plus, he’s a Republican minister who could be considered liberal.

He’s somebody who I think is an interesting vehicle to talk about where we can agree in terms of what kind of society we want to have; that was really part of my motivation for wanting to make the film. That, and then just the emotional component of it too, that what Fred Rogers was trying to do was attack fear. I think he saw fear as the most corrosive element in our human psyche because fear festers into hate and anger and resentment. If you can address the fear you can promote the love. I felt like that was another message that would be good conversation to have right now.

Absolutely. I was born in 1979, and Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood was such a big part of my childhood, but with watching your movie, I forgot about how he addressed really important social issues, like the assassination of Robert Kennedy, or the Vietnam War in a way that children could understand.

Those are specific heavy examples, but he was tackling really tough issues regularly. I think what he did that was so unique at the time, and is still kind of unique in television history, is that he never condescended to children, that he understood that children knew when bad things were happening. He wasn’t going to tell them to sweep it under the rug. He was going to help them process it, which is a much healthier thing to do than telling kids not to worry about things.

Definitely. You include a critique of Mr. Rogers from Fox and Friends, who call him “an evil, evil man” and kind of the start of the “participation trophy” culture. I don’t think that was a critique coming from a place of good faith, so I’m wondering why you included it in the film.

In part because it was probably one of the biggest critiques that existed of him while he was alive, but I think it’s also a common gross misunderstanding of what he was trying to say, which is not that we praise children because they’re entitled to a sense of worth but that there are more children who feel that they are worthless and to know that every life has some worth, and that for a child who may not have a parent or not who might be essentially being raised by somebody like Mr. Rogers to understand that they’re worthy of being loved.

I think really that’s fundamentally what he’s trying to say, and fundamentally that’s the very idea of grace. It’s a very Christian idea, too. It’s that every human is worthy of our attention and goodness, because they’re all created in the image of God. I felt like that was a corrective that needed to be made.

And you interview an African-American gentleman who was on the show…

Yes! One of the most moving, to me, moments in the film came when you showed Mr. Rogers and Francois Clemmons together in a wading pool, with their legs next to each other. But there was also a moment where you talked to Francois going to a gay bar and Mr. Rogers telling him that he can’t go back or he can no longer be on the show. I thought that was interesting because he understood how damaging it would be to the show in an era as racist and homophobic as the 1970s were…

Yeah. I think Fred was very quietly progressive in his ideas. By doing a scene with Francois Clemmons and him in a kiddie pool and sharing water together it was a very subtle way of modeling what appropriate behavior is. I think he did that consistently throughout the show, but he also was always struggling with how far ahead of the times to be and how far that if you got too far ahead of the times that he could lose the most important thing to him, which was the sanctity of the show.

There’s another example that’s not in the film but I thought it was interesting, that Fred was a pacifist. In the Gulf War a couple of the cast members, like Francois, became very outspoken anti-war. Fred refused to because he thought that there could be children watching the show whose parents were fighting in that war. For him to speak out against that war would make those children feel unwelcome. I think the thing he was trying to do was, again, protect the show, even if it came at some personal cost.

It’s not in the movie, but there was a story in Tom Junod’s profile for Esquire, where a young man with cerebral palsy met Mr. Rogers, and Mr. Rogers asked him to pray for him, rather than tell the boy “I’ll pray for you.” It’s one of those moments that I keep coming back to and thinking about all the time.

He was so smart about those things. By asking a disabled child to pray for him you’re asking somebody who always felt like a victim to be empowered that they could do good for somebody else. That is just so intuitive and smart.

He had many disabled kids on the show, not just Jeffrey Erlanger, but nobody has done that really before, or since. To him, he said he hated the term disabled, because he said it’s defining somebody by their inability to walk or talk or something else. He said the real disabled people are the people who live in depression or bitterness. Those are the people he considered disabled.

{Won’t You Be My Neighbor? is playing in theaters now. In Seattle, it can be found at SIFF Cinema Uptown, Meridian 16, and Lincoln Square in Bellevue.}