Benediction (2022 | UK | 137 Minutes | Terence Davies)

In what’s becoming an ongoing series of autobiographically-influenced autobiographies of influential poets, British director Terence Davies follows up his stirring 2016 portrait of Emily Dickinson (A Quiet Passion) with the story of decorated turn-of-the-century war poet Siegfried Sassoon. Marked by themes of homosexuality, dalliances with catholicism, and quests for redemption, elements of writer’s life echo many of Davies’s regular touchstones, making for an especially resonant examination of the deeply aching curse of having borne acute witness to decades of great suffering, both the world’s and one’s own inner turmoil.

Organized as a series of loosely connected flashbacks, we first meet the poet in his later days, on the verge of an unexpected conversion to catholicism. As embodied by an ever-acerbic Peter Capaldi, he is a figure of enduring exactitude whose grasp at unchanging permanence through a late-life religious transition baffles his adult son. The ensuing two hours represent an attempt to explain the gnawing agony of the enduring observational remove paradoxically required for both self-preservation and deep perception.

But it’s hardly as glum as all of that, even if it is permeated by a mournful tone. Most of the film takes place in flashback, where Jack Lowden (recently of the excellent AppleTV+ spy series, Slow Horses) takes the reins as the poet as a young man, having returned to England from the horrors of the Western Front. Despite his decorations for courage on the battlefield, an even greater act of bravery comes in the form of a blistering letter explaining his refusal to perform further military duties. Aiming to shake the government and press into re-evaluating the conduct of the war and the lack of clarity of its objectives, some combination of his existing fame as a poet and political favors from a well-connected family friend grants him a stay in a Scottish war hospital in place of a court martial.

Having been diagnosed with “a mind in chaos”, it’s there that we begin a tour of both Siegfried’s reckoning with the traumas of war (punctuated by gory archival footage narrated by Sassoon’s poetry) as well as his ongoing series of gay adventures with the bright young things of 1920s England. Despite the illegality of homosexual acts, the era also seems to have a typically British attitude of willfully ignorant tolerance so long as it avoids making too much of a fuss. We see this both in his candidly evasive, ever-confident wordplay with his similarly “anomalous” and sympathetic psychologist at the institution as well as with the intimate friendship he strikes up with another quiet writer undergoing rehab. Davies leaves most of the steamy bits offscreen, instead relying on Lowden’s unshowy performance to fill in the quiet longing, silently reading a heart-piercing poem (that we won’t hear until much later), stifling a reaction to learning that his doomed friend will be going back into service just in time for Christmas, and refusing to make their parting more painful. It’s a testament to the acting and filmmaking that these scenes of dewy tennis courts and chaste handshakes carry such emotional weight.

Eventually, the war ends, and the widely acclaimed poet makes a splash among the aristocracy and artistic circles alike. There, several well-connected mentors and his own acclaim gain him entry to rarified realm of tuxedoed parties, literary salons, and the glamorous theatre world. Chief among the affairs enabled by this tolerant crowd is an ongoing relationship with a sneering star of musical theater, the “cruel-eyed” pretty boy Ivor (Jeremy Irvine). It’s easy to buy Lowden’s Sassoon as handsome and witty enough to make a cheesy dreamboat want to snatch him up from across a room, but most of the messy bits are kept under the surface. Aside from one scene when a night of passionate betrayal spins the relationship carousel, the loose disconnection of the storytelling and the intentional emotional remove leaves much of the depth of feeling and specificities of the flesh to the imagination. It’s a choice not necessarily made out squeamishness, but one that conveys the sense that the magnitude of pain beheld during wartime exhausted Sassoon’s emotional reserve and left him reflexively guarded.

As such, the film seems desperately allergic to melodrama in any form, so much so that as it flits through his biography Siegfried’s decision to marry a woman comes as jarring surprise. Perhaps had the multi-year, Covid-delayed production been converted to a limited series, each of these emotional attachments and compromises could’ve been given greater depth, but instead Davies relies on a return to the older Sassoon and Capaldi’s capacity to embody the hollowed regret of a lifetime of choices, long-held grudges, and the immense weight of being unable to turn away from a self-appointed responsibility do justice to it all through language, just as Davies has accepted a similar mantle through film.

Benediction opened in theaters on June 3

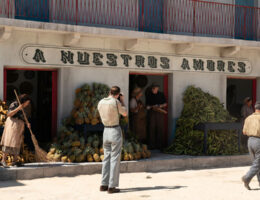

Header image courtesy Roadside Attractions.