Triangle of Sadness (2022 | Sweden | 143 minutes | Ruben Östlund)

Ruben Östlund is a master satirist of the follies of the rich and the extents to which minor grievances become seismic irritants. Force Majeure saw a husband’s instantaneous response to impending danger unsettle a marriage, The Square found absurdity in the patronage society of the art world. With his second Palme d’Or winner Triangle of Sadness, his daggers are somehow sharper and his targets make even worse company. If you’re going to do social satire that’s this broad, it had better be diamond-edged and drowning in the vomit of the those whose absurd wealth stems from the most banal pursuits. Triangle of Sadness has too much of both, plus a beautiful male model who cares very deeply about who’s turn it is to pick up the tab for dinner.

Told in three acts, our constant guides on this doomed tour are upstart models Carl (Harris Dickinson) and Yaya (Charlbi Dean). He’s had his centerfold moment, but is still trying to book runway campaigns through a mastery of a walk and scowl; she’s reached higher echelons and benefits from the rare inverted pay structure of an industry where women far out-earn their male counterparts. The conclusion of a fancy dinner after a fashion show becomes a clinic in performative gender and economic politics as the two beauties argue without arguing about whose credit card gets splashed in the shiny metal tray. Östlund lives for these small battles and lets it run to agonizing lengths with close camera swings tracking the exchange of verbal and psychological blows at the table, an awkward ride home, and air their grievances in a dimly-lit hotel room.

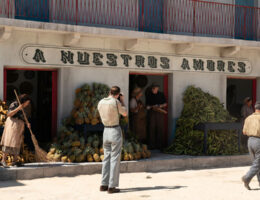

Some time later, the couple find themselves on a luxury yacht. They’re riding for free on her influencer status; the lone breath of youth among a decaying collection of rich people, each of whose fortunes have been made in ever-more boring or offensive fashion. An unnaturally cheery telegenic crew attends to their every petty concern with a polished performance of competent servitude among the sparkling seas while an invisible platoon of service workers tend to the messes below. When the conspicuously absent captain (Woody Harrelson) finally makes his appearance, the scene is set for one of the grossest dinner sequences I have ever seen. Amid comedically rocky waters, quivering confections of high culinary art contend with widespread seasickness. Gastrointestinal agony contends with a broadcast of a boorish blotto conversation between the Marxist sea captain and a Communist capitalist whose empire was literally (and proudly) built on shit. The ordeal goes on forever, punishing the audience and characters alike and inducing a clamor for escape.

In satires like this, nothing goes according to plan, at least as far as its hapless characters are concerned. The final act finds a handful of the guests lampooned on a deserted seashore, struggling to survive. Sunbaked and useless, the social order is swiftly upended to a hierarchy in which competence rules and the disintegration and desperation induce a kind of slick pleasure. We’re still stuck with these people, but at least they aren’t having any fun either. It’s here that Dolly de Leon, as a member of the ship’s tireless and underseen cleaning staff, emerges as one of the film’s most clever performances as the others, including consummate survivor Dickinson scamper to adapt. The message isn’t subtle, but its delivered with such enthusiasm from the cast’s embodiment of their distasteful characters and the director’s relentless amplification of agony that it builds to a delirious success. The word “uproarious” may be used too often, but there were parts of this movie where I was literally screaming along with the rest of a crowded theater in disgust and clapping as the dynamics among characters twisted. Its perspective is pitch black and its methods less nuanced, but sometimes the follies of inequality require a very sharp stick.

A version of this review initially appeared when Triangle of Sadness (NEON) had its North American premieres at the Toronto International Film Festival. It is now playing in wide release, including a stint at SIFF.