Saturday is when Telluride gets really real: wake up early, take a brisk walk to the theater, and get a place in the queue. There, diligent festival volunteers dispense numbered laminated cards an hour before showtime that dictate the order for pasholders to shuffle into the theater beginning a half hour before showtime. If you’re lucky, you’ll have enough time between getting a card and needing to return to scramble into town to get a morning coffee, preferably at Ghost Town, accompanied by one of their exceptionally delicious fancy toasts (I dream about the avocado, tomato, pesto one all year). With less time to dilly-dally, try a grab-and-go breakfast burrito at The Butcher and the Baker or an efficient espresso at the Phoenix Bean.

For true believers aiming to maximize their passes, this process repeats for the next three days, and strategic planning can allow you to make each day a five movie marathon. The less devoted, though, might slack off for one movie slot to allow time for a proper meal or a rooftop cocktail (when you go, The New Sheridan’s Roof is a good place to start, where you’re bound to see a festival guest or two grabbing drinks after their premieres. The freshly-opened roofdeck at The Last Dollar is also a hugely welcome addition to the town).

My Saturday was a four film affair — a world premiere, a North American premiere, plus two Cannes catch-ups.

That early wake-up call was to see Waves, a semi-surprise release from director Trey Edward Shults for the festival season. Anticipated for well over a year with few updates since early reports speculated that it was going to be a musical, it turned out to be one of the more special movies to debut at Telluride this year. It did not, however, turn out to be a musical in the singing and dancing sense. Instead, it’s a lyrical and propulsive drama with a killer score from Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross and a showstopping soundtrack of contemporary hits (Kanye West, Tame Impala, Radiohead, a whole lot of Frank Ocean).

We open in the life of teenage wrestler (Kelvin Harrison, bleached blond), racing through daily drives on vertiginous Miami causeways, speeding in packed cars under saturated blue skies, waking up to go to early morning practices, enduring the long school day, rigorous evening practices, quiet watercolor weekend dates at the beach, and battling through high intensity competitions. The whole sequence is dazzling, a barely broken shot from a rotating camera that never sits still until a the whole family piles into a booth at a diner for breakfast after church. Sterling K. Brown plays a father who’s not shy about his high expectations for his son and his unwillingness to tolerate anything but the best. The next hours unfold with with hyperkinetic camerawork, vibrant colors, and heart-wrenching performances, following this well-off high-pressure family breathlessly into a crisis and then, in what almost feels like a different movie (with Lucas Hedges and a breakout performance from Taylor Russell) , through the slow unsteady bloom of catharsis.

A tough, but moving hang. ☆☆☆☆

Family Romance LLC The main clue that Werner Herzog’s latest film is an inspired-by-real-life dramedy and not a documentary is the absence of his always-phenomenal drolly accented narration. Instead, in this slim film, filmed in Tokyo with non-professional actors, he explores Japanese surrogate culture through a series of vignettes centered around a (real) man whose (real) company provides impostors for hire. Inspired by an article on the rent-a-friend boom in Japan, which profiled Ishii Yuichi and his actual business Family Romance LLC, we see the many personal reasons that people seek his services. A bride can’t bear to have her alcoholic father attend her wedding; a salaryman can’t bear to take the blame for his train scheduling mixup; a would-be influencer wants to feel what it’s like to be at the eye of a paparazzi storm while boosting her social stats; a retiree longs to recapture the thrill of winning a contest.

Most of these jobs are one-offs, a quick fix for an inconvenient deficiency in personal lives. But amid these odd jobs, we also follow Yuichi taking on the role of father-for-hire to a shy twelve-year-old girl. Her successful single mother decides that she needs a paternal figure and, too busy to develop a new relationship and too estranged to reach out to the long-absent biological father, outsources the job. It’s all very efficient — a meet-cute at the cherry blossom festival (he in a formal business attire, she in a dragon-horned hoodie), regular visits to the park, and soon outings with her little friend to an adorable hedgehog cafe — all with regular debriefs with mom afterwards to provide insights on her daughter. But as the fake relationship develops, the feelings become too authentic for comfort, causing Yuichi to question the nature of his own reality. The gentle narrative with humorous and tender insights on another culture made the slim 90 minutes feel like a nice breather amid an already hectic festival. ☆☆☆½

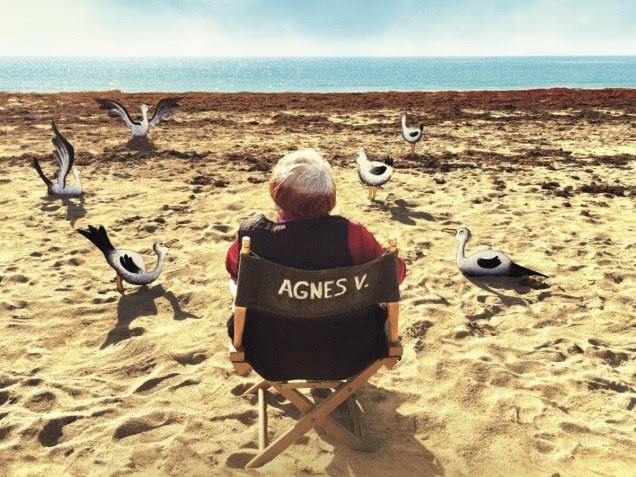

The screening of Varda by Agnès was preceded by a panel paying tribute to the New Wave master that featured her children (Rosalie and Mathieu Demy, both involved in her films), Telluride Film Festival founder Tom Luddy (who worked with Varda in the 1960s in San Francisco), and an obscure filmmaker named Martin Scorsese, who flew into the mountains just to pay tribute to his longtime friend. Over nearly an hour, each of them extolled her virtues and the inseparability of her work from her life. Scorsese called her a god.

But as moving and inspirational as it was to hear these stories, plaudits, and context for her voracious sense of curiosity and spirit of innovation, it turns out that the best person to talk about the work of Agnès Varda herself. Although she died early this year, her final film does exactly that, assembling clips from her greatest works — narrative and documentary film, large scale artworks, and experiential exhibits — accompanied by a series of talks to eager audiences. But soon, ever embracing her creative spirit, the narration escapes the formal setting of theaters and lecture halls. One sequence, in which she describes a series of shots in Vagabond, while essentially recapitulating those shots sitting aboard a large dolly on tracks through a farm until meeting the star of that movie all of those years later, brought a tear to my eye and took my breath away.

Unsurprisingly, the film has many moments like these, providing one final bow for an infinitely curious and inventive master to once again experiment with form while at the same time delivering the definitive annotated lecture of her own diverse humanity-elevating career. A moving retrospective, and an invitation to revisit an impressive catalogue (or, for many, to experience it for the first time). ☆☆☆☆

The last event of my long day, was a tribute to Adam Driver, whose clip reel was surprisingly longer and more impressive than I expected when it was announced that he was receiving one of the festival’s two Silver Medallion Awards (the other was for Renée Zellweger). Fresh from fêting Agnès Varda, Martin Scorsese made a surprise appearance to heap praise on Driver and share a few stories from the grueling experience of filming Silence. It feels like the beginning of an Oscar campaign and I (and the also surprising number of Star Wars fans in the audience) are here for it. Marriage Story is one of three films that Driver has coming out this fall (the other is very good torture-investigation docudrama The Report, which premiered at Sundance and played again here in the mountains); but it’s easily his best shot at a statue.

Marriage Story is Noah Baumbach’s evenhanded and semi-autobiographical chronicle of the slow-motion horror of a divorce starring Adam Driver and Scarlet Johansson. We first meet the couple — him, a successful producer on the rise; she, a former Hollywood teen actress who’s settled into the lead role in his experimental theater company in New York — through very romantic his-and-hers montages detailing everything that they love about each other. These turn out not to be love notes, but a homework assignment to bring to a mediator who’s expecting to preside over their impending separation.

Their enduring affection for each other initially makes it hard to see why they’re even splitting up. What they initially envision to be an amicable, if sad, “conscious uncoupling” slowly becomes more and more complicated by the contentious questions of custody over their young son and the realities of bicoastal living. As these issues grow insurmountable, real lawyers get involved (Laura Dern is simultaneously ruthless and cozy as her high-powered attorney; a droll Alan Alda is his warm ramshackle counsel), the longstanding faults in their relationship become ever more apparent.

Baumbach doesn’t exactly take sides, though you get the sense that Driver gets the more sympathetic edit as the guy whose attempts to remain affable are eventually ground down by reality. In moments big and small, though, the film has a series of utterly devastating performances from Scarlett Johansson and Adam Driver, jokes about the ridiculousness of California, and this one other utterly phenomenal thing that’s best left a surprise. It left me a quivering mess. ☆☆☆☆☆