Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2020 | New Zealand | 103 minutes | Justin Pemberton)

Like countless millions, I haven’t yet gotten around to reading French economist Thomas Pikkety’s bestseller about wealth and capital. An apparent page-turner, the English translation climbed to the top of the New York Times’s nonfiction list in 2014 and became the biggest success in the history of Harvard University Press. Luckily, though, not doing ones reading assignments now works as well for histories of income inequality as it always has for popular fiction and the book has been adapted into a compact and coherent film.

Certainly, director Justin Pemberton can’t be expected to capture the depth and nuance of a 700 page treatise with an efficient hour and forty minutes, but spending time with the engaging documentary felt more that sufficient preparation to navigate heady cocktail parties with a conversational level of fluency. The crash course opens and closes with words from the author himself, but much of the “talking heads” work of the film is delegated to a coterie of other young, telegenic, rising stars of economics, academics, history, and journalism (Gabriel Zucman, Suresh Naidu, Gillian Tett, Kate Williams) along with a Nobel laureate (Joseph Stiglitz) and an ender of history (Francis Fukuyama) for good measure.

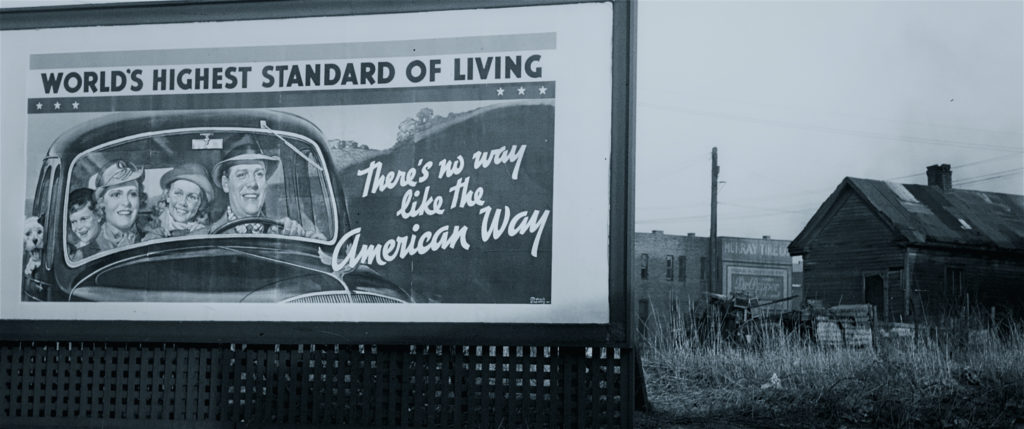

Their commentaries are the glue for a collage of historical footage and film clips assembled to illustrate a sprightly jaunt through the economic history of Europe and the United States from the eighteenth century to the present day. Everything is glossily assembled, accessible, and the soundtrack is on point. A montage scored by Lorde’s “Royals” sets the stage for the quick rewind from modern signifiers of wealth and faith in unregulated markets all the way back to the times of Pride and Prejudice with the chasms of inequality secured through the pernicious role of land ownership and inheritance in consolidating (and expanding) generational wealth. It’s a brisk clip from the revolutionary era of Les Misérables (the one with the singing) through mobility on the frontiers of the “new worlds” of Australia and the United States and onto the vast social upheavals that expanded workers’ rights and voter participation following the first World War. Before we get to comfortable with the rise of wealth and fashion to fuel new economies, a clip from Grapes of Wrath introduces the Great Depression, government safety nets (that were politically preferable to the rise of Communism), as well as a nationalistic “Make Germany Great Again” ethos that gave rise to Hitler, Nazis, and a worldwide conflict that claimed millions of lives, ravaged cities, and erased vast amounts of capital while also birthing the dreamlike 1950s with a surging middle class and unprecedented social mobility.

Of course nothing gold can stay (and wasn’t even gold for everyone anyway). Dolly Parton’s “Nine to Five”, Michael Douglas’s absurdly lionized turn as Gordon “Greed is Good” Gekko, and the Weeknd’s “The Morning” are among the cultural signposts on our way through Stagflation, Wall Street’s cannibalization of Main Street, Regan and Thatcher’s fetishization of 19th century economics, and globalization’s ability to offer us nice things on the cheap while allowing corporations to divorce profits and workforces from geography. Soon enough, we’re in the near-present, on the heels of deregulation, the bursting housing bubble, global financial collapse, unregulated spending influencing elections, and (again) surging wealth inequality and consolidation of capital.

The film is far more than pop culture references and snappy transitions. For its broad scope, there’s surprising depth among the decade-hopping and economic theory. There’s a chilling psychological experiment in which college students play Monopoly, one randomly allocated advantages of fortune and movement, that illustrates the alacrity with which inherited wealth warps self-perception. A look at China provides some insights into modern state capitalism, broad (but still unequal) growth, a (now realistic) focus on improving life for one’s children, and a new locus of social mobility. Throughout, data and theories are presented cogently and compellingly, ultimately conveying the inherent dangers of capital essentially existing nowhere, growing faster in fewer hands, and avoiding taxation that would support the infrastructure that it relies upon.

Ultimately, Pikkety’s prescriptions — progressive taxation of capital tethered to a geography of consumers rather than the locus of incorporation, reducing the influence of capital on democracy, and limiting generational transfers of wealth — feel both self-evident and fantastical. But while the outlook feels grim (and was made before our current catastrophe), the film succeeds by provides a visceral sense of the long sweep of history, the dynamics that have prompted progress, and maybe even some reasons to look for opportunities for change, especially in the wake of a crisis. ☆☆☆☆

Capital in the Twenty-first Century is available for home viewing through a collaboration that shares proceeds between KinoNow and local theaters including Seattle’s Grand Illusion (through March 14).